In late March, 1945, on the southern banks of Italy's Senio River and barely 500 hundred meters from the German front, soldiers of the Jewish Brigade took part in a Passover Seder. Not surprisingly, they found special meaning in the words that they read and the songs that they sang. As the first Jewish force since the time of the Maccabees, they had two major missions ahead: participation in an Allied assault which would free the remnants of their Jewish brethren in Europe – and the future battle for a Jewish State.

Formed at the tail end of the Second World War, and only after non-stop pressure by Chaim Weizmann in London and the Jewish Agency in Palestine, the Brigade consisted of 5,000 (mostly Palestinian) stalwart Jews fighting under the Zionist flag and proudly wearing a Star of David insignia on their shoulder patches. Incredibly, Jewish volunteers from the tortured Land of Israel were getting superb military training that would be put to good use both in Europe and later on, at home. Their mettle had already been tested under fire, with several of their comrades killed in skirmishes with the Germans. And only a few days after the Seder they would join other soldiers in a massive push into Italy.

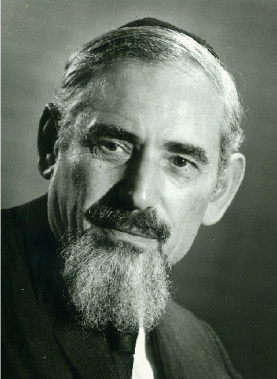

Conducting the Seder (along with two more that same night) was Captain Bernard Moses Casper. The Seder would become one of the high points of an extraordinary life, which climaxed with his appointment as the first Chief Rabbi of South Africa in 1986 and ended with his passing just 23 years ago.

Born in Britain, Captain Casper lost both of his parents at the tender age of three; the grandparents who took him in died only a few years later. The cousin who began caring for Bernard when he was eight sent him to both secular and Jewish schools, where he immersed himself in education. At 17 he won a scholarship to Cambridge and, while attending university, also began rabbinical studies.

During the massive bombardment on London in 1940, Casper was living in Manchester where he was appointed the Manchester Synagogue's Congregational Leader, or Reverend (he had not yet been ordained as a rabbi). But World War II was wreaking havoc on Europe and soon afterwards, although he had recently fathered a son, Casper enlisted in the British Armed Forces.

Reverend Casper's first assignment consisted of chaplaincy duties in England, but he was soon ordered to Egypt where he was stationed with a support unit from Palestine serving behind the lines. That changed when, upon formation of the Jewish Brigade, he was thrilled to become Brigade chaplain.

The Germans surrendered in May –but neither the Brigade nor its chaplain had yet fulfilled their destinies. Soon after the German defeat, while the Brigade was stationed near the border triangle of Italy, Yugoslavia and Austria, military police brought a Hungarian refugee into the camp. Starving, barely able to stand, struggling to get the words out, he told Captain Casper that 150 Jews were huddled in railroad cars at a bombed-out city just over the Austrian border. And they had no one to help them. . .

Captain Casper had formed excellent relationships with the British military police and area officers. Armed with a pass to get him through the trip, he filled a truck with provisions. Then he and a Brigade driver high-tailed it into Austria and distributed their food and supplies.

The very next day Captain Casper led a convoy to Klagenfurt, filled the vehicles with refugees, tricked the border police into letting him and 150 hidden passengers into Italy, and returned to camp.

Like Captain Casper, others in the Brigade were also carrying out rescue operations. However, a great many of these postwar activities were against military regulations. After caring for over 8,000 survivors during the next few weeks, the Brigade was transferred to Belgium and disbanded the next year. Captain Casper returned to Manchester, England, where he continued his former duties as Congregational Leader. In 1948 he traveled to Israel, where he completed his rabbinical studies and received semicha.

Although he wanted desperately to remain in Israel, his wife Kitty's family obligations kept the Caspers in England. There, he became head of Jewish Education and then Rabbi of London's historic Western Synagogue.

In 1956 Rabbi Casper was finally able to bring his family to Israel. Bombarded with tempting offers of high level positions in the Foreign Ministry, and asked to become head of the famous Kadouri Agricultural School, the rabbi chose, instead, to take a position as the first Dean of Students at the Hebrew University. His selection was a wise one, for Rabbi Casper was not only imbued with religious spirit but perfectly at ease with, and wholly respectful of, the secular world.

Then, seven years later, he was invited to become Chief Rabbi in Johannesburg, South Africa and had to decide where he could best serve the Jewish nation. On the advice of Israel's Chief Rabbi, he took the job in Johannesburg. A passionate and charismatic advocate for Israel in South Africa, he also worked tirelessly to enrich Jewish education for pupils in public schools and to preserve the Jewish identity of South Africa's Jewish community.

From far away South Africa, however, Casper was also trying to improve the quality of life in Israel. While in Israel, he had been deeply concerned about the country's impoverished neighborhoods, especially Jerusalem's Bukharan Quarter, and during his years in South Africa he set up a special fund for their improvement.

Project Renewal, a far-reaching urban revitalization program, was established by Prime Minister Menachem Begin in 1977. It depended heavily on income from the Diaspora, and suggested pairing well-to-do Jewish communities with destitute populations in Israel. Generous Johannesburg was twinned with the dilapidated Bukharan Quarter, and the Jews of that city raised enormous funds for its rehabilitation.

But time went by, and projects planned with vigor and enthusiasm became bogged down in Jerusalem's bureaucratic hassles. Nothing was happening, so in 1981 Rabbi Casper – always a man of action – set off for the Holy Land to get a first-hand look at the problem.

After examining the situation, and consulting with community organizer Moshe Kahan, Rabbi Casper suggested a solution: they would present the dormant agencies with concrete evidence of what could be done! Using a private discretionary fund, he initiated development of several pilot projects, among them a free loan fund, a dental clinic and a hearing center whose wild successes embarrassed the municipality into getting its act together. (Today the City provides a facility with municipal social services offering their full cooperation.)

All of the projects eventually combined to become the Health and Community Service Center, with clinics in the Bukharan Quarter and a state-of-the-art facility in downtown Jerusalem established by P.E.F. Israel Endowment Funds, Inc. of New York which also subsidized the free, top-quality dental care for children from needy families from grade school to age 18 provided by today's center, and which has already treated thousands of Jerusalem children. There has been a ripple effect, as well, for the HCS which is now celebrating three decades of service has become a model for community service throughout the State of Israel. (See the video:Three Decades of Care with Compassion)

The 10th of Teveth marks one of the fast days remembering the destruction of Jerusalem and also Yom HaKaddish HaKlali. It is also the day marking Rabbi Casper’s Yahrzeit. It is no mere coincidence that this loving son of Jerusalem who longed to participate and indeed did participate in the beginnings of her rebuilding should be recalled together with Jerusalem on this occasion each year.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About the background music: Shir Ha'Emek (Song of the Valley)was written by Nathan Alterman and performed here by The Parvarim. Rabbi Casper mentions this song in his book "With the Jewish Brigade". On board the ship that was to take them from Egypt to the Italian Front, Casper writes:

That night after supper, as we lay out in the harbor waters some distance away from land, we began to gather on the quarter-deck. Little was spoken; soon a song broke out on someone's lips, and in a few minutes a thousand men had joined in the chorus. The singing grew in volume as we squeezed up into a massed, rough but harmonious choir. The songs seemed never-ending. For hours we must thus have given freedom to our hearts and voices. It was now quite dark; the ship was completely blacked-out; the blue Mediterranean was now visible only as a black shiny surface. But we were thinking of Lake Kineret, of the waters off Tel Aviv beach; of the Emek lying beneath just such a starry sky. The Song of the Emek rose again and again in our concert- "Ba'a Menuchah Layagea", "Rest has come to the weary"; "Numa Emek, Eretz Tifereth, Anu Lecha Mishmeret', "Rest peacefully, O Emek, O you beautiful Land; we are guarding you."

The order comes for bed. "Clear the decks!" We stand, as one man, to attention (though nobody has said a word about it), and sing "Hatikvah". We are on the way to the ghettos and camps of Europe with our message of hope.